Cases of canine influenza linked to imported rescue dogs from Asia.

At Christmas time, Jessica Mantoani opened her home in San Carlos, California, to a beautiful Golden Retriever from South Korea in need of a foster family.

Mantoani, having volunteered for years with the nonprofit, Doggie Protective Services, recalls feeling proud that her local rescue organization focused on saving animals from Korea’s dog-meat trade, by bringing them to the United States.

Two days after he arrived, he was coughing and would spit up white, goopy stuff onto the floor,” she recounted. Mantoani guessed it was a mild case of kennel cough.

The rescue group took the dog to be treated for an upper respiratory infection and returned him to her home. Then Mantoani’s younger dog, Sheldon, stopped eating, started coughing and became lethargic. Her two elderly Jack Russell terriers, Bailey and Tildon, also became ill — gravely so.

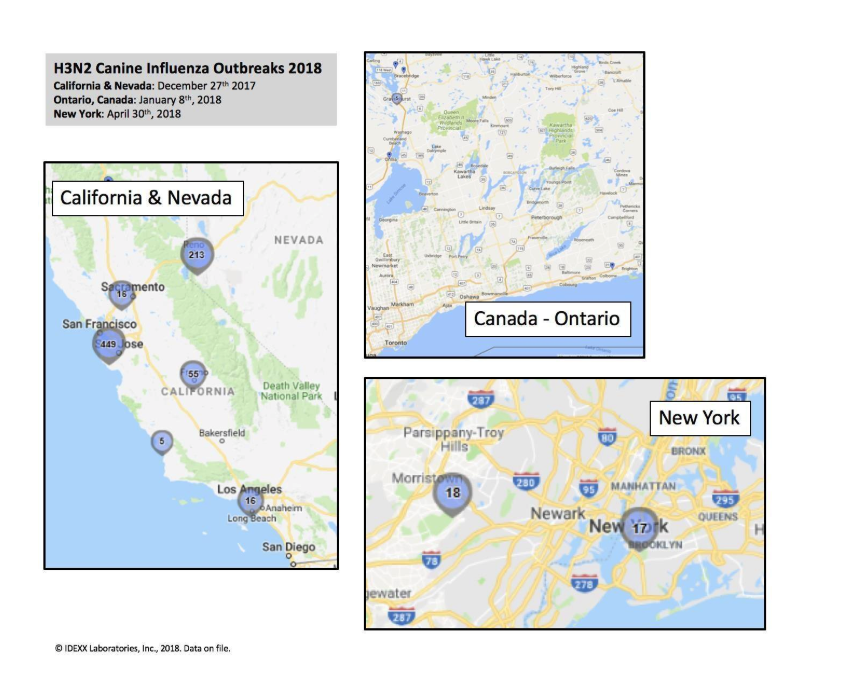

On New Year’s Day, 11-year-old Tildon began vomiting and having seizures. After a harrowing trip to the SAGE Centers for Veterinary Specialty & Emergency Care in Redwood City, the dog perished. Mantoani later learned that the golden carried H3N2; a virulent, potentially deadly strain of canine influenza, that public-health experts say is being spread to the United States, from infected dogs imported from foreign countries.

Officials with the nonprofit told a news station in Ontario, the dogs had been quarantined for three months in South Korea, before making the overseas trip and they had “no way of knowing” the dogs were ill.

In the United States, thousands of dogs have tested positive for the disease since it first appeared in the country in Chicago, in 2015. Researchers traced the Chicago outbreak to canine influenza virus circulating among dogs in South Korea. Last month, more than three dozen H3N2-positive dogs were identified in and around New York City.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now considers H3N2 to be endemic in the U.S.

In Canada, Ontario had its first 2018 cluster of cases in the Orillia area, followed by cases in multiple locations north of Toronto. Since then, there have not been any more H3N2 cases in April and May 2018. Our flu outbreaks have been confined, and as far as we can tell, canine influenza has been eradicated in the country. This is known since we have seen no new cases for a period well beyond the incubation and shedding period for this virus.

In 2004, when Cornell University’s Animal Health Diagnostic Center helped isolate the first flu subtype: H3N8, found to sicken dogs. Today, at least two subtypes are known to infect dogs: H3N8 and H3N2. The first is believed to have jumped from horses to racing greyhounds and moved on to the general canine population. Illness from H3N8 appears to have all but burned out in the United States. In its place, is the more virulent and deadly H3N2. Researchers identified the avian-origin H3N2 canine influenza virus five years ago, circulating in farmed dogs in Guangdong, China.

Last week, researchers raised another argument for strengthening canine-importation requirements. In a study published June 5 in Mbio, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology, scientists report having demonstrated that the H1N1 flu virus — a potentially deadly subtype of influenza that’s responsible for sickening humans, can jump from pigs to canines. Should H1N1 mix in dogs already carrying H3N2 or H3N8, the reassortment could result in a novel zoonotic version of the flu, the study says. That means dogs might one day be the source of a global flu pandemic, the researchers warn.

Dr. Camille Fischer, a veterinarian in Redwood City, California, believes the relatively benign nature of the first known dog-flu subtype: H3N8, has led the public to become nonchalant about canine influenza in general. “H3N8 is our model of a disease that’s smouldered in our communities,” Fischer said. “[Because] it’s a lot less dangerous to dogs than H3N2 is … it’s led people to be complacent [about] H3N2.” The differences between these two viruses is dramatic. H3N2 is much deadlier.”

Taken from a June 11, 2018 report of The Veterinary Information Network (VIN) News Service

Written by Dr. Alex Hare, DVM